Public Data Shows that LAPD Stops and Arrests are Racially and Economically Biased, Costly for Communities, and An Inefficient Means of Advancing Traffic Safety

Contents

Introduction

Report Publication Date: 05-04-2021

In response to decades of racist policing carried out by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), a broad cross-sector coalition of base building, advocacy, and faith-based organizations joined together in 2019 to demand an immediate end to the LAPD’s racist policies and practices. This coalition, known as Promoting Unity, Safety & Health in Los Angeles (PUSH LA), has tirelessly worked to seek an end to the LAPD’s use of pretextual stops to racially profile low-income communities of color and an immediate removal of the LAPD’s Metro Division from South Los Angeles. The City of LA needs to immediately end the use of pretextual stops because they are extremely dangerous and harmful for low-income communities of color, are neither an effective nor efficient means of advancing community safety, and are a wasteful misuse of vital public resources.

Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, PUSH LA, along with other grassroots movements and organizations—including Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, and The People’s Budget LA—joined tens of thousands of Angelenos in the streets to call for an end to the LAPD’s systemically racist policies and practices. Those protests included demands to, among other things, shift the LAPD’s $3 billion annual budget to non-law enforcement community supports and services, and end racial profiling and police brutality.

In response to that movement, the Los Angeles City Council (City Council) introduced a series of police reform motions in June 2020. Amongst those was a motion (Council File No. 20-0875)—authored by Councilmembers Marqueece Harris-Dawson, Mike Bonin, Curren Price, Herb Wesson, and David Ryu—which calls for a study to explore alternative models of traffic safety that do not rely on armed law enforcement (the “Traffic Safety motion”).1 The motion also acknowledges the disproportionate impact of the LAPD’s racially biased policing, and provides that “law enforcement agencies nationwide and here in Los Angeles have long used minor traffic infractions as a pretext for harassing vulnerable road users and profiling people of color.”2 A pretextual stop occurs when an officer stops a person in order to investigate them without actual evidence of a crime, and identifies an alleged traffic violation as the legal basis (pretext) for the stop. For years, Black and Brown Angelenos have had to endure these degrading pretextual stops and the attendant dehumanizing trauma, harassment, and unjustified uses of force that all too often arise as a result.

As evidence of such lived experiences, in October 2020, the Los Angeles Office of Inspector General (OIG), and California Policy Lab (CPL) issued separate reports that detail the LAPD’s practice of disproportionately subjecting Black and Latinx people to vehicle stops and searches compared to Whites, even though searches of Whites are more likely to result in recovering contraband or evidence of a crime, or give rise to an arrest.3

In February 2021, the City Council passed the Traffic Safety motion, and the required study on alternative models and methods is now in progress.4 Against this backdrop, the current report—produced by Advancement Project California’s RACE COUNTS initiative on behalf of the PUSH LA coalition—uses racial and economic equity lenses to shed further light on the devastating impact of the LAPD’s discriminatory practices. This report adds to existing research by evaluating disparities in the use of traffic stops both citywide and by City Council District. It also analyzes disparities in arrests for vehicle code charges.

This report addresses five primary research questions for LA City as a whole and by Council District:

- What are the racial disparities in vehicle stop and arrest rates?

- What are the class disparities in vehicle stop and arrest rates?

- What was the time spent by LAPD police officers on stops for traffic violations in 2019? (LA City only)

- What was the total number of vehicle stops made by LAPD Division and Bureau?

- How do vehicle stops and arrests compare to vehicle collisions?

Key Findings

A significant number of people are subject to traffic stops by the LAPD annually. The data show that there are stark racial disparities in vehicle stops and arrests of people of color, primarily Black and Latinx Angelenos, compared to Whites. Black and Latinx Angelenos are disproportionately stopped and arrested by the LAPD compared to White Angelenos, and lower-income Black communities in particular are overburdened by LAPD stops and arrests. There are also racial disparities in the time spent on traffic violations with LAPD officers spending the most time on stops of Black individuals. These trends are generally consistent across Council Districts, but the particulars vary.

- Compared to White individuals, Black individuals are 5 times more likely to be stopped and nearly 9 times more likely to be arrested for traffic violations than White individuals. Similarly, Latinx individuals are 1.6 times more likely to be stopped, and 3.5 times more likely to be arrested for traffic violations than White individuals.

- We found that traffic stop rates are positively correlated with poverty rates. This means that as poverty rates increase, traffic stops increase as well. However, when controlling for neighborhood poverty—by, for example, comparing stops of White and Black people in the same neighborhood with the same poverty rate—the data show that people of color are disproportionately stopped and policed at all income levels. In other words, neighborhoods with high rates of poverty for Black people experience a higher rate of traffic stops than neighborhoods with high rates of poverty for White people.

- LAPD officers spend a significant amount of time on stops for traffic violations—totaling 183,616.3 hours on stops for traffic violations between January and September 2019.

- Officers spend more time on traffic violation stops of Black and Latinx individuals compared to Whites. These racial disparities persist when focusing on minor traffic offenses, such as those where the result is only an infraction, warning, or no action. For example, officers spent over 22 minutes on 25% of stops involving Black people resulting in only an infraction, warning, or no action. Comparatively, the same top 25% threshold for White people was only 15 minutes.

- Traffic Service divisions generally conduct the most stops for the City and most Council Districts. In many districts, a higher share of stops made by non-traffic divisions are of people of color compared to the distribution of stops made by traffic divisions.

- Across LA City, vehicle collision rates are moderately correlated with arrest rates for vehicle code charges and strongly correlated with vehicle stop rates. However, the strength of this correlation varies by Council District. For instance, Districts 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 have a weak correlation between vehicle collision rates and arrest rates. This means that higher collision rates do not translate to higher arrests for vehicle charges, and vice versa. In Districts 3 and 5, we see low arrest rates even as vehicle collision rates increase.

- Reporting on race and ethnicity in law enforcement data obscures trends for certain groups. We found that individuals identified as ‘Other’ by LAPD officers have some of the highest stop and arrest rates. The disproportionate rates among this group points to issues in reporting of race and ethnicity in law enforcement data where race and ethnicity are based on LAPD officers’ reports, rather than self-identification by the persons involved in each incident. This can lead to inflated rates for the group ‘Other’ and deflated rates for other groups if officers are more likely to misidentify people of color or multiracial individuals as ‘Other’.5

These findings underscore the harm and disproportionate impact of stops on Black and Brown communities in Los Angeles, especially lower-income Black communities. These disparities are present to some degree across all Council Districts and have direct implications for the community and personal costs of traffic stops. Higher stop rates in low-income communities of color mean that socioeconomically vulnerable Angelenos are likely being routinely taxed through fines and fees for minor traffic offenses they cannot afford to pay.6 A base fine for speeding, for example, can amount to $100. On top of that, numerous fees and penalties are added—to fund a variety of government services and projects—that increase the actual citation costs to nearly $500. If a person gets sick, cannot miss work, or is unable to make it to court for another reason, an added $300 civil assessment may be imposed to bring the total cost to over $800. And, on top of that, the person’s driver’s license can be suspended until all of the fines and fees are paid.7 The harms of biased stops and arrests have implications for the City as a whole—not just people of color—because they also impose high public costs in the form of time and resources spent on activities that do not necessarily lead to more traffic safety. These biases and inefficiencies are detrimental to people that the LAPD swore to serve and protect.

Methodology In Brief

The analysis below is based on a combination of LAPD data and the California Department of Justice’s (CADOJ) Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) data to detail disparities in stops and arrests. While the CADOJ RIPA data provides a detailed view of stops that allows us to narrow down to stops for traffic violations, it provides limited information on where stops occur. Therefore, for neighborhood and Council District-level analyses, we rely on stop data published by the City of Los Angeles and the LAPD on the city’s Open Data Portal, which does not include the reason for the stop. Depending on the data source, our analysis either includes all vehicle stops or only stops for traffic violations. For arrests, we only include arrests for vehicle code charges related to Moving Traffic Violations or Miscellaneous Other Violations.8

To arrive at estimates for Council Districts and neighborhoods, we rely on geographic units used by the LAPD in reporting and patrol—called reporting districts and Basic Cars. We use reporting districts included in stop and arrest data to aggregate up to Council District boundaries. We use Basic Cars to approximate neighborhoods and calculate neighborhood-level estimates like poverty and collision rates. Basic Cars are smaller neighborhood units of the LAPD’s 18 Community Police Stations.9

We focus on stops and arrests between 2018 and 2020, using three-year averages. For any analysis of CADOJ RIPA data, we focus on the 2019 year.

Limitations in Brief

Race and ethnicity in stop and arrest data is based on LAPD officers’ reports, rather than self-identification by the persons involved in each incident. Officer perceptions of the people they stop are the proper lens to use for purposes of understanding racial profiling. However, this means that the stop and arrest rates for certain groups may be depressed, or in some cases absent, due to misidentification by officers. In other words, when we combine total population estimates from the American Community Survey, which is based on self-identification, with data based on officers’ reports, we can end up with rates not fully reflective of the experiences of every group. This can also lead to inflated rates for the group ‘Other’ if officers are more likely to misidentify people of color or multiracial individuals as ‘Other’. This approach of combining data based on officers’ reports with demographic data based on self-identification, however, is not inconsistent with standard methods for analyzing data on racial and identify profiling.

Download our Detailed Methodology for more information.

LA City Report

Racial Disparities in Stops & Arrests

All Angelenos have the right to live peacefully in their communities without facing unjust traffic stops. In a report examining traffic stops made by the LAPD in 2019, the OIG found evidence of racial bias in stops by the LAPD.10

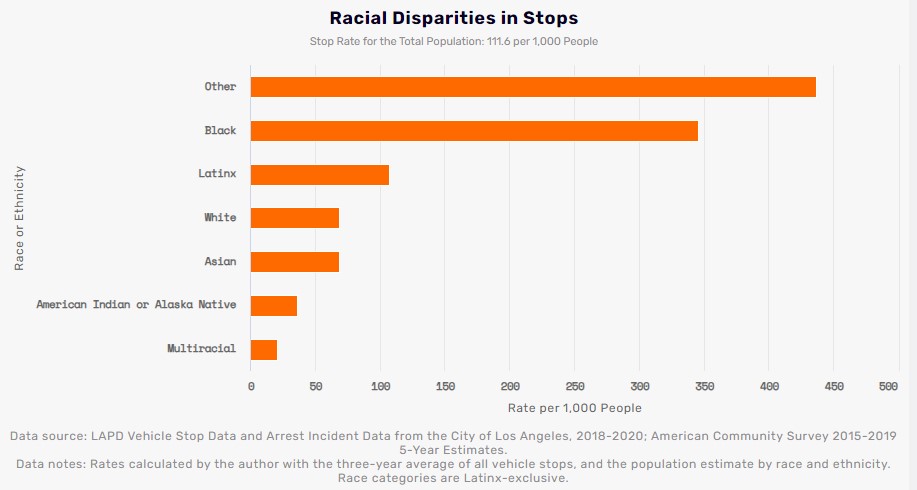

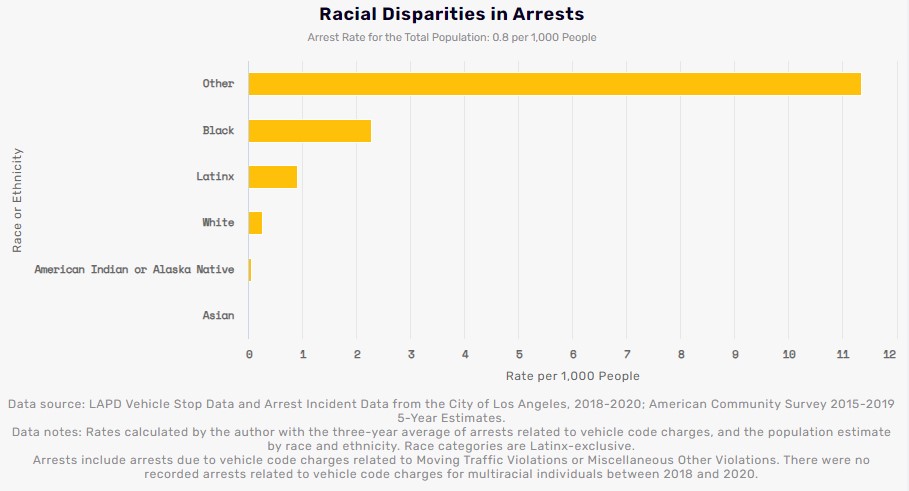

We analyzed data on LAPD stops and arrests, specifically arrests for vehicle code charges, from 2018-2020 to examine the impact of racially biased policing in the city as a whole. We calculated the rate of vehicle-related stops and arrests by race and ethnicity and compared the rates for Angelenos of color to the rate for White Angelenos.11 Overall, our analysis confirms that people of color, primarily Black and Latinx Angelenos, are disproportionately stopped and arrested by LAPD compared to White Angelenos. It also shows a disproportionate impact on Angelenos identified by officers as another race, or ‘Other’.

- There are substantial racial disparities in traffic stops and arrests made by the LAPD. Individuals of another race (categorized as ‘Other’), Black and Latinx residents are most likely to be stopped or arrested.

- People of color, especially Black people, are disproportionately stopped and arrested in Los Angeles. While 8.6% of the city’s population is Black, 27% of LAPD traffic stops are of Black people. Conversely, 28.5% of the city’s population is White, but only 18% of LAPD traffic stops are of White people.

- Black Angelenos are 5 times more likely to be stopped by the LAPD than White Angelenos.

- Latinx Angelenos are 1.6 times more likely to be stopped than White Angelenos.

- Black individuals are nearly 9 times more likely to be arrested than White individuals. Latinx individuals are 3.5 times more likely to be arrested than White individuals.

Class Disparities in Stops & Arrests

Unjust and racially biased traffic stops can economically devastate communities of color by subjecting them to fines and fees that they cannot afford. This perpetuates cycles of poverty rooted in systemic racism endemic to our society. We analyzed LAPD stop and arrest data (2018-2020) along with neighborhood poverty rates12 in order to examine class disparities in traffic stops in addition to racial disparities. We calculated the relationship, or correlations, between poverty rates and stop and arrest rates by race and ethnicity in each Basic Car. We specifically included only arrests for vehicle code charges related to Moving Traffic Violations or Miscellaneous Other Violations.

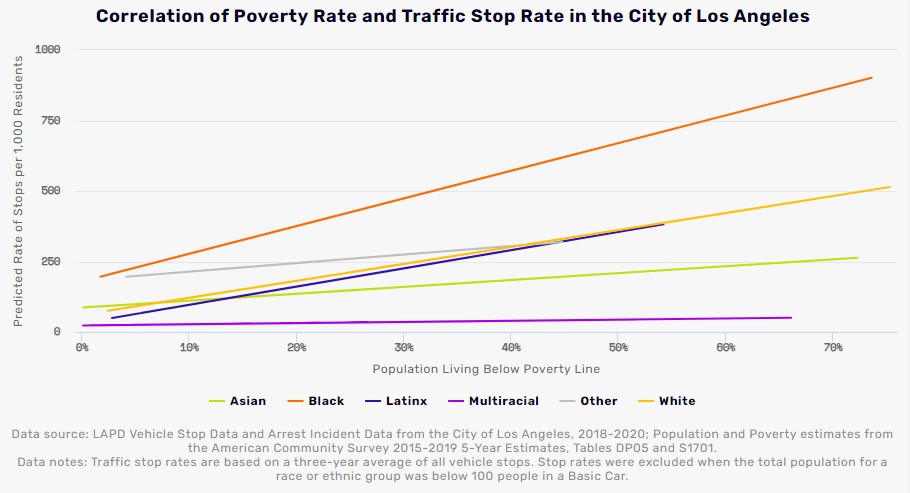

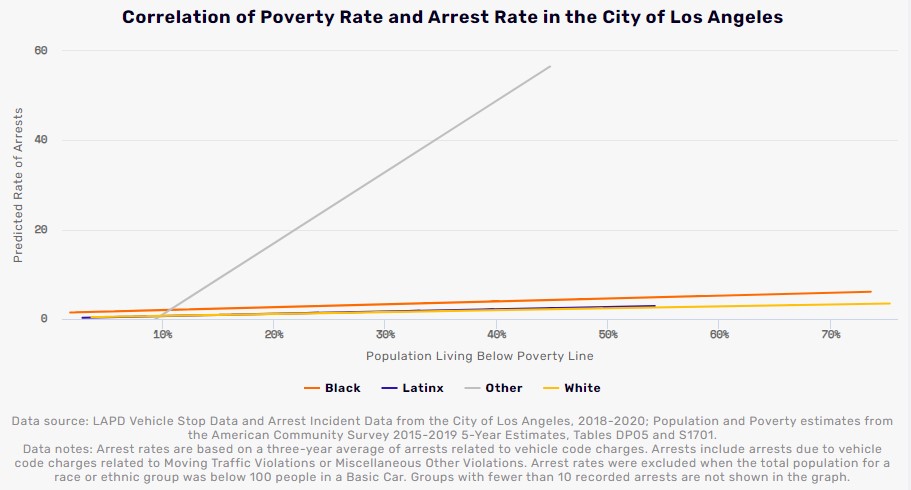

Our analysis found that while lower-income communities overall are overburdened by LAPD stops and arrests, Black low-income communities in particular carry the burden of economically biased stops, and Black and Latinx low-income communities carry the burden of economically biased arrests.

Across neighborhoods in the city, we found positive correlations between stop and arrest rates and Asian, Black, Multiracial and Latinx low-income Angelenos, meaning that as poverty rates increase, so do stop and arrest rates. We also found a positive correlation between White low-income communities and the rate of stops and arrests of White residents. In the case of traffic stops, White low-income communities had a slightly stronger correlation with poverty rates than Black low-communities, as Black communities face higher rates of traffic stops and arrests at all income levels.

The trend lines show the relationship between the rate of traffic stops and the share of the population living below the poverty line, for each race or ethnic group.13

Correlation describes the degree to which two sets of numbers move in the same direction. A positive correlation means that the numbers move in the same direction. For example, a positive correlation between the traffic stop rate and the poverty rate means that as the traffic stop rate increases, so does the poverty rate.

- In the City of Los Angeles, traffic stops are positively correlated with poverty, meaning that as the share of people who live below the poverty line in a neighborhood increases, the rate of traffic stops increases as well.

- However, not all people in lower-income communities share the burden of traffic stops equally. Black low-income residents shoulder the brunt of the burden of traffic stops.

- Traffic stops are positively correlated with all low-income residents. This means that as the share of low-income residents in a community increases, the rate of residents who are stopped by LAPD increases as well.

- The traffic stop rate for White people has a slightly stronger positive correlation with the poverty rate for White people, as there is a stronger relationship between poverty and White traffic stops, whereas Black neighborhoods are generally over-policed no matter the poverty rate.

- Arrests disproportionately affect Black and Latinx low-income residents. Low-income Black communities face a substantially higher arrest rate than other groups at all income levels; low-income Latinx communities experience higher arrest rates than White communities at higher rates of poverty.

Inefficiencies & Time Spent on Stops

To add to the data available on racial inequities in stops and arrests, we examined the effects of stops from an efficiency viewpoint. Traffic stops account for a significant amount of officer time and, in turn, entail a significant use of public resources. Evidence of both inequities and ineffectiveness of traffic stops raises additional questions and concerns about how they are used and who conducts them.

We first looked at the efficiency of stops by analyzing CADOJ RIPA data on stop duration for all stops and comparing time spent on stops by stop type and race and ethnicity. We then looked at the sheer number of stops conducted by LAPD Bureau using LAPD data on all vehicle stops to determine which Bureaus conduct the most stops and how the demographics of these stops compare. Lastly, we compared the arrest and stop rates by Basic Car to traffic collision rates.

Time Spent On Stops

We summarized the total time officers spent on stops as well as the the range of time spent on stops for traffic violations by race and ethnicity. We focused on stops for traffic violations and stops for traffic violations that specifically led to relatively minor results, including only a citation, warning, or no action. These likely represent stops purportedly conducted in furtherance of traffic safety goals, but instead serve as pretext for profiling and harassment, particularly when the time spent on stops is longer.

- LAPD officers spend a significant share of their time on stops on stops for traffic violations: Between January and September 2019, LAPD officers spent a total of 300,748 hours on pedestrian and vehicle stops. Of these hours, 183,616.3 hours, or 61.1%, were spent just on stops where the reason listed for the stop was a traffic violation (e.g. moving, equipment, or non-moving violation). Of these hours spent on traffic violations, 81,274.1 hours (44.3%) were spent on stops that only resulted in a citation, 43,257.5 hours (23.6%) on stops with only warning issued, and 17,421.9 hours (9.4%) where no action was taken.

- LAPD officers on average spend less time on stops for traffic violations: The average amount of time an officer spent on a traffic violation was 23.2 minutes.The average amount of time spent across all stops, including traffic violations, was 30.6 minutes. The amount of time spent on traffic violation stops was similar whether a citation or warning was issued. When no action was taken, officers spent an average of 26 minutes on the stop. This suggests there are some traffic violation stops where no action is taken where officers are spending a longer amount of time on the stop compared to the average time for other traffic violation stops.

- LAPD officers spend more time on traffic violation stops involving a Black individual compared to any other racial group: LAPD officers spend the widest range of time on stops for traffic violations involving Black individuals, with stops ranging from 1 minute to over 2 hours. While 75% of stops involving a White individual take under 15 minutes, 75% of stops involving a Black individual take under 25 minutes. In other words, LAPD officers spend less time on stops of White drivers than Black drivers across the range of stop duration. There are similar disparities for Latinx, Multi-Racial, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Pacific Islander individuals. This provides further evidence of racially biased policing in traffic stops and suggests the use of stops as a pretext for profiling and harassment.

- Controlling for stops that only resulted in an infraction, warning, or no action, LAPD officers still spent the most time on stops of Black, followed by Latinx, individuals: LAPD officers spent less than 22 minutes on 75% of stops involving Black individuals where the result of the stop was either an infraction, warning, or no action. They spent less than 20 minutes on 75% on similar stops involving Latinx individuals. Comparatively, 75% of stops of White individuals with the same result took less than 15 minutes. This reiterates racial disparities in traffic stops where the actions taken and time spent on traffic stops of the same type are noteably different between people of color and Whites due to racially biased policing and unequal treatment from officers.

Total Stops Conducted

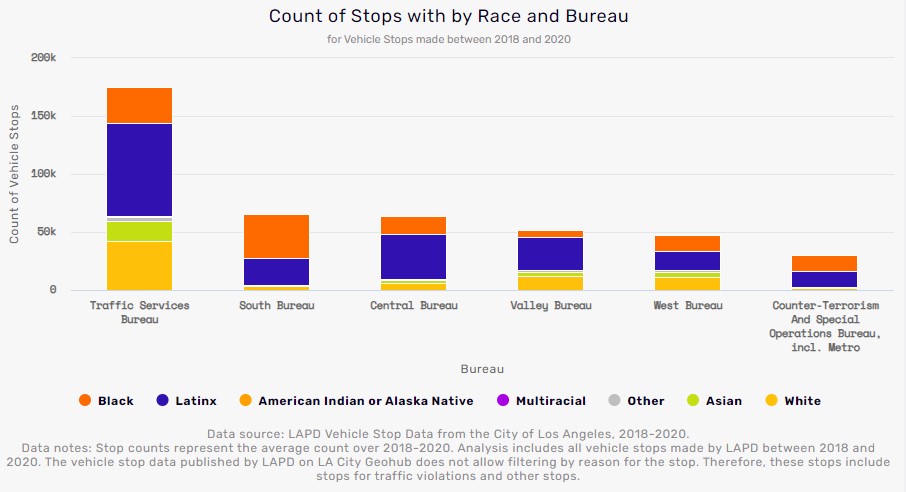

Using vehicle stop data published by the LAPD, we analyzed the number of vehicle stops made each year by race and LAPD Bureau.16 Showing stops by Bureau, we see which Bureaus conduct the most stops each year and which racial groups are most impacted by these encounters with law enforcement. The dataset published by the LAPD does not specify the reason for the stop. These data points are only available in the RIPA data which is limited in its information about the officers (including the Bureau or Division officers are assigned to) and the place where the stop occurred.

The chart below includes the six Bureaus that made the highest number of stops between 2018 and 2020.

- The Traffic Services Bureau conducted the most stops: Between 2018 and 2020, the Traffic Services Bureau completed an average of 175,061 stops per year. The majority of these stops were of Latinx drivers (45.8%).

- The South and Central Bureaus conducted the next highest number of stops: The South and Central Bureaus conducted an average of 65,468 and 63,538 stops per year between 2018 and 2020, respectively. Less than 10% of stops for each of these Bureaus are of White individuals.

- Black individuals are over represented in stops across all Bureaus compared to their share of LA City population: Black individuals comprise 8.6% of the LA City population.17 However, they made up 17.8% of stops made by the Traffic Services Bureau. For stops made by the South Bureau, they made up 57.3% of stops, and for stops made by the West Bureau–an area covering Mid-Wilshire, Hollywood, and West Los Angeles–28.4%. Comparatively, just 24% of stops made by the Traffic Services Bureau were of White individuals though they make up 28.5% of the city population.

- The Counter-Terrorism and Special Operations Bureau, which includes the Metropolitan Division, conducted a high number of stops of Black individuals: The Counter-Terrorism and Special Operations Bureau conducted more stops of Black individuals than either the Valley or West Bureaus–an average of 13,826 stops per year, or 45.8% of all their stops.

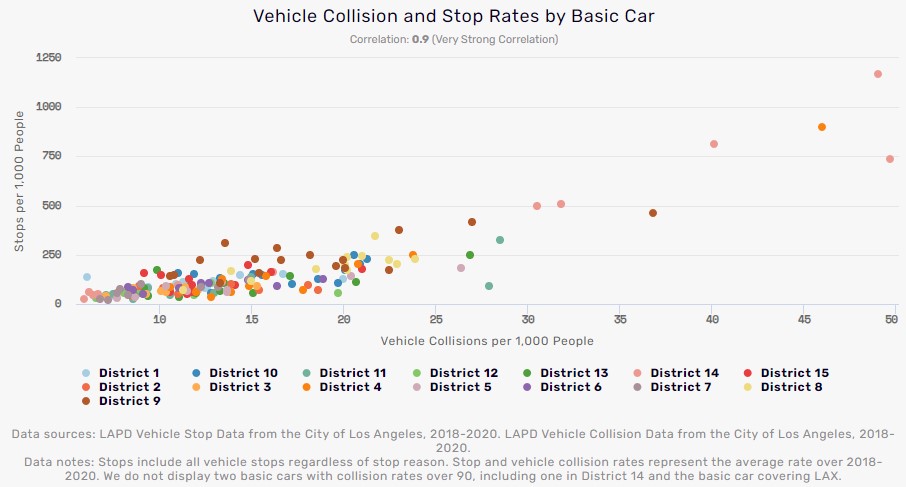

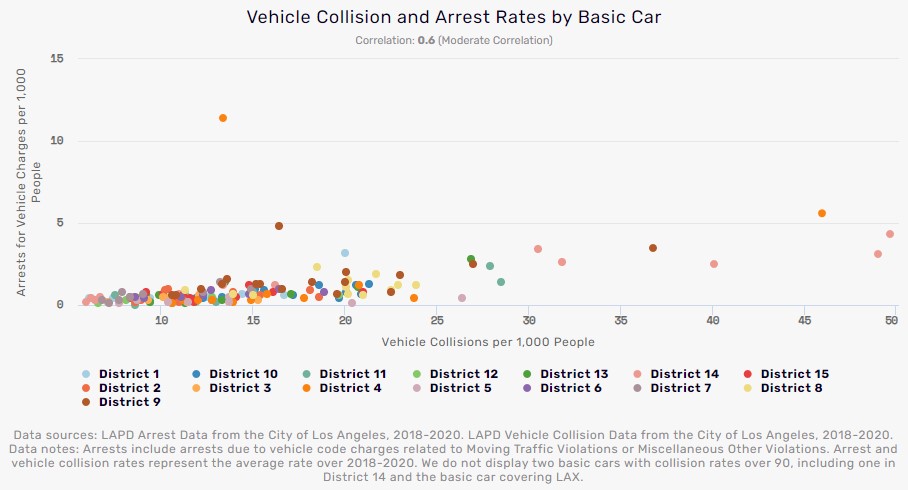

Stops & Arrests Compared To Collisions

We compared vehicle collision rates to stop and arrest rates at the Basic Car level to identify whether there is a positive relationship, or correlation, between the areas where traffic collisions and vehicle stops and vehicle code-related arrests occur. 18 This analysis cannot determine causation, including whether stops and arrests have reduced or increased traffic collisions in an area. Rather, it can tell us whether we can expect stop and arrest rates to increase when traffic collisions increase, and vice versa.

- Arrest rates are moderately correlated with vehicle collision rates: Across LA City, vehicle collision rates are moderately correlated with arrest rates for vehicle code charges. In other words, as vehicle collision rates increase, arrest rates increase. However, the strength of this correlation varies by Council District. Districts 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 have a weak correlation between vehicle collision rates and arrest rates. Moreover, the correlations for Districts 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 15 are not statistically significant, meaning we cannot say that the relationship between collisions and arrests is not due to chance.

- Stop rates are strongly correlated with vehicle collision rates: Across LA City, vehicle collision rates are strongly correlated with vehicle stop rates. In other words, as vehicle collision rates increase, stop rates increase. However, the strength of this correlation varies by Council District. Districts 2 and 12 have a weak correlation between vehicle collision rates and stop rates and their correlations are not statistically significant, meaning we cannot say that the relationship between collisions and arrests is not due to chance.

Council District Profiles

Click on a Council District from the list below to see how these disparities appear in each district.

- Council District 1

- Council District 2

- Council District 3

- Council District 4

- Council District 5

- Council District 6

- Council District 7

- Council District 8

- Council District 9

- Council District 10

- Council District 11

- Council District 12

- Council District 13

- Council District 14

- Council District 15

Recommendations

LAPD vehicle stops for minor traffic violations impact thousands of people of color annually, and make up a sizeable share of all stops and officer time that could be replaced with alternatives that do not waste public resources or expose communities of color to unnecessary contact with armed law enforcement. In light of the findings from this report and prior studies, LA City should continue to pursue alternative traffic safety models—as provided for under the Traffic Safety motion—that do not rely on armed law enforcement. Recent approaches to reform—such as de-escalation and implicit bias training, body-worn cameras, and modifying LAPD agency policies—are helpful starting points. However, both data and the lived experiences of low-income Angelenos of color show that deeper systems change is long overdue. Below is a comprehensive set of policy recommendations that should be adopted.

- Immediately End the Use of Pretextual Stops: A pretextual stop occurs when an officer stops a person to investigate them without actual evidence of a crime, and identifies an alleged traffic violation as the legal basis (pretext) for the stop. For years, Black and Brown Angelenos have had to disproportionately endure pretextual stops and the attendant dehumanizing trauma, harassment, and unjustified uses of force that all too often arise as a result. In addition to causing such unjust harm, research shows that pretextual stops—especially those based on minor equipment or regulatory violations—have limited effectiveness in actually identifying evidence of crimes.19

- Immediately Remove the LAPD’s Metro Division from South LA: Both data and the lived experiences of Black and Brown low-income Angelenos show that the Metro Division has had a devastating impact on people in South LA. The Metro Division’s harmful presence in that community should immediately end by no longer having officers from that Division in South LA.

- Enhance Urban Design to Improve Traffic Safety: Rather than relying on the LAPD, it is time to reimagine traffic safety through alternative models and methods that address the root causes of circumstances that create traffic safety risks. For example, instead of using a punitive approach through issuing fines (an ineffective deterrent) for speeding, urban design investments – such as adding more speed bumps, stops signs, and clear street markings – could be adopted to prevent speeding in the first place, which would, in turn, minimize the overwhelming economic impact of excessive fees extracted from low-income Angelenos of color.

- Equitably Address the Root Causes of Traffic Safety Issues: Imagine a low-income person has a broken taillight or another vehicle maintenance issue. What if instead of having an armed police officer pulling that person over to issue a ticket – which could lead to another unnecessary episode of police violence – unarmed traffic safety city employees are there to provide the driver with a voucher that they can take to a mechanic in their neighborhood to cover repair costs? This service would help the driver who cannot afford to repair their vehicle, improve roadway safety, and support the economic viability of small businesses. This preventative, problem-centered approach to addressing the root causes of public safety—rather than using law enforcement as a default response to every social problem—is far from new. There is a growing movement, for example, to have unarmed mental health specialists, rather than police, respond to people experiencing a mental health crisis. For people without housing, it is now well-understood that it would be better for them to have ongoing relationships with trained social workers instead of police officers. A similar—non-law enforcement—approach to traffic safety has the potential to save millions of Angelenos of color from the LAPD’s systemically racist—and all too often traumatizing and deadly—policies and practices. It would also enable vital public resources to be redirected to fund services and supports that respond to the needs of LA’s most underserved communities.

- Hold Officers Accountable for Misconduct: Officers who engage in racial profiling, unjustified uses of force, or other misconduct should be disciplined and removed from communities that are predominately low-income and of color.

- Ban Vehicle Consent Searches: Research shows that consent is often listed as the basis for searching a person even though consent was not actually provided, not provided voluntarily, or that the person did not understand that they had a right to refuse consent. 20 For people of color, such unjust searches routinely amount to unnecessary trauma and harassment, especially when combined with pretextual stops. Because of such problems, jurisdictions around the country have banned consensual searches. LA City should do the same. 21

Conclusion

The LAPD’s approach to traffic stops disproportionately harms low-income Black and Latinx communities. These disparities are present to some degree across all Council Districts. As a result, in addition to non-monetary harms—such as being subject to unjustified uses of force, trauma, stigma, and dehumanization—many socioeconomically vulnerable Angelenos are routinely taxed through fines and fees for minor traffic offenses they cannot afford to pay. The monetary and non-monetary harms of these stops and arrests have implications for Angelenos and the economic vitality of all Council Districts. Furthermore, data suggest that the LAPD’s racial and economically biased approach imposes high public costs in the form of time spent on numerous stops and arrests that do not necessarily lead to more traffic safety. These biases and inefficiencies are detrimental to people that the LAPD swore to serve and protect. Fundamentally transforming LA’s systemically racist and economically unjust approach to policing can no longer afford to wait. The lives and dignity of far too many Black and Brown and low-income communities are at stake, as well the long-term viability of LA City’s budget—which for far too long has been absorbed by the LAPD’s excessive budget.

Acknowledgements

Research and data analysis by Elycia Mulholland Graves and Laura Daly.

Written by Chauncee Smith, Elycia Mulholland Graves, and Laura Daly.

Conceptualization support from the PUSH LA coalition.

Editing support from Katie Smith and Karla Pleitez Howell.

Design and page development by Rob Graham and Katie Smith.

Citations

To view the full text of the motion, visit: https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2020/20-0875_mot_06-30-2020.pdf. ↩︎

Los Angeles City Council File No. 20-0875. Retrieved from https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2020/20-0875_mot_06-30-2020.pdf.↩︎

Owens, E.& Rosenquist, J. (2020). RIPA in the Los Angeles Police Department: Summary Report. California Policy Lab. Office of Inspector General. (2020) Review of Stops Conducted by the Los Angeles Police Department in 2019.↩︎

Los Angeles City Council File No. 20-0875. Retrieved from https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2020/20-0875_rpt_ahpr_10-23-20.pdf.↩︎

For more information, please visit our Detailed Methodology↩︎

Annette Case & Jhumpa Bhattacharya. “Driving into Debt: The Need for Traffic Ticket Fee Reform.” Insight Center for Community Economic Development, May 2017. Retrieved from https://insightcced.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/insight_drivingintodebt.pdf.↩︎

“Stopped, Fined, Arrested: Racial Bias in Policing and Traffic Courts in California.” Back on the Road (CA) Coalition, April 2016. Retrieved from https://lccrsf.org/wp-content/uploads/Stopped_Fined_Arrested_BOTRCA.pdf.↩︎

Miscellaneous violations include a range of charges, from tampering with a vehicle to driving without an interlockdevice, to littering on a highway.↩︎

Basic Cars are geographic units approximating neighborhoods, for more information see the LAPD Basic Car Plan online:https://www.lapdonline.org/search_results/content_basic_view/6528↩︎

Los Angeles Police Commission, Office of the Inspector General, Review of Stops Conducted by the LAPD in 2019. https://www.oig.lacity.org/significant-reports↩︎

We focus on the rate for White Angelenos as the comparison given that overwhelming research on racially biased policing suggests White individuals are least impacted by police stops and uses of force. Additionally, while other racial groups at times have lower rates, their rates may be underreported due to misidentification by officers or the lack of disaggregated data to capture disproportionate impact by subgroups, specifically Asian subgroups.↩︎

Neighborhoods were approximated with LAPD Basic Cars. To see a map of LAPD Basic Cars, visit: https://geohub.lacity.org/datasets/1c5090ae270f4d878ae108b0e87a4c37_0.↩︎

The trend line shows the predicted rate of traffic stops associated with the poverty rate for each race and ethnic group, based on a linear model (Stop Rate ~ Percent Poverty) of the stop rate in each Basic Car (n = 169) and the poverty rate in the Basic Car (by race/ethnicity).↩︎

The trend line shows the predicted rate of arrests associated with the poverty rate for each race and ethnic group, based on a linear model (Arrest Rate ~ Percent Poverty) of the arrest rate in each Basic Car (n = 169) and the poverty rate in the Basic Car (by race/ethnicity).↩︎

Stop incidents represent unique stops. More than one person can be included in a stop in CADOJ RIPA data. For analysis of stop incidents, we pulled unique stop incidents rather than duplicating stops that involved more than one person, but were still the same stop—and thus the same time spent by officers.↩︎

For a map of regional Bureaus in LAPD, visit https://www.lapdonline.org/inside_the_lapd/content_basic_view/6468. For a listing of all Bureaus, visit https://lapdonline.org/inside_the_lapd/content_basic_view/1063.↩︎

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2015-2019.↩︎

LAPD Basic Cars are used to approximate neighborhoods. To see a map of LAPD Basic Cars, visit: https://geohub.lacity.org/datasets/1c5090ae270f4d878ae108b0e87a4c37_0.↩︎

Office of Inspector General. (2020) Review of Stops Conducted by the Los Angeles Police Department in 2019.↩︎

Office of Inspector General. (2020) Review of Stops Conducted by the Los Angeles Police Department in 2019.↩︎

R.I. Gen. L § 31-21.2-5(b) (2014). Peter Yankowski, “5 Things to know about CT Police accountability law.” CT Post. Oct. 1, 2020. https://www.ctpost.com/local/slideshow/Photos-from-article-CT-police-accountability-law-210080.php↩︎